What is aperture in photography? It’s one of the fundamental elements of any picture, if not the most important camera setting you’ll make. Controlling the amount of light that hits your camera’s sensor isn’t the only role of that big hole in your lens. It also enables you to get creative with depth of field.

In this tutorial we’ll not only answer the question of ‘What is aperture’; we’ll show you how to use your camera’s aperture to start getting creative with light.

So what is aperture exactly?

Put simply, the aperture is a hole in the lens that light passes through to reach your camera’s imaging sensor. You use aperture, shutter speed and ISO in combination to create an exposure.

Aperture’s role in this mix is to control how much light reaches the sensor. With the exception of a very few ‘fixed aperture’ mirror lenses, all camera lenses allow you to change the size of this hole so that more or less light can pass through it.

Why would I want to alter how much light reaches the sensor?

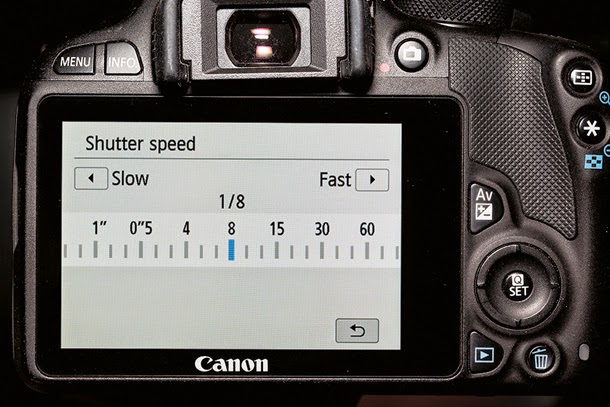

Well, let’s look quickly at the other elements of exposure: shutter speed and ISO. The choice of shutter speed dictates how long the camera sensor is exposed to the light that passes through the aperture.

It also has a bearing on how movement is captured in your shots; faster shutter speeds enable you to freeze it, while slower shutter speeds allow you to add ‘motion blur’ for a more artistic result.

If lighting conditions and the camera’s ISO setting – which determines how sensitive the sensor is to light – remain constant, then the only way to ensure the sensor receives enough light to make consistent exposures as the shutter speed increases and decreases is by opening and closing the aperture.

As shutter speed gets faster (creating a shorter exposure time), the aperture needs to become wider (to increase the intensity of light).

As shutter speed gets slower (creating a longer exposure time), the aperture needs to become smaller (to reduce the intensity of light). It’s all a question of balancing these two elements.

I’ve heard photographers talk about using ‘wide’ and ‘small’ apertures – what do they mean?

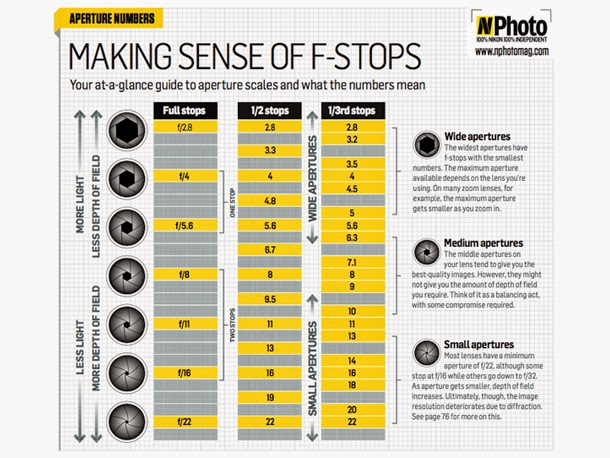

Those terms refer to the size of aperture being used. It’s a bit confusing, because the widest apertures correlate to the smallest f-stop numbers (such as f/2.8 and f/4).

However, when a photographer says they’re using a ‘small aperture’, they actually mean they’re using f-stops with the highest numbers (f/16, f/22, and so on).

If you think of the aperture as a fraction instead of an ‘f-stop’, it makes more sense.

For example, 1/4 is bigger than 1/16, so an aperture of f/4 will let more light in than f/16.

As well as affecting exposure, your choice of aperture also gives you control over the depth of field in an image – and this is one of the most potent weapons in the creative photographer’s arsenal.

Depth of field…?

OK, think of depth of field as a zone that extends in front of and behind the point of focus in which elements still appear acceptably sharp.

By reducing the depth of field, you can make a precise part of a shot appear in sharp focus and allow other areas to become blurred.

This enables you to draw attention to key parts of the image, and conceal elements that might otherwise prove distracting.

Increasing the depth of field, conversely, has the opposite effect, making more ‘layers’ in a scene appear sharp.

While depth of field in a photo is influenced by several factors, including focusing distance and focal length of the lens, in terms of aperture selection it boils down to this: the wider the aperture you use, the less depth of field you capture; the smaller the aperture you use, the more depth of field you capture.

Or to put it another way, big holes equal more background blur, small holes equal more sharpness.

So, when would I need to take control of the aperture?

The choice of aperture is the most important consideration for a whole range of shooting situations.

For instance, landscape photographers typically use small apertures with wide-angle lenses to give their pictures as much depth as possible.

That’s how they achieve those detailed scenics in which all the elements, from flowers at their feet to mountains on the horizon, are rendered pin-sharp right throughout the frame.

Portrait and wildlife photographers frequently opt for the other end of the scale, using long lenses and wide apertures to sandwich a sharp subject between blurred foreground and background.

Aperture becomes even more of a crucial consideration as you get close to a subject. The nearer you focus, the less depth of field will be captured for a given aperture.

This is why macro photography requires the use of precise focusing and very small apertures, as depth of field can often be measured in millimetres.

I should use Aperture Priority mode all the time then, right?

When control over depth of field is important to an image, then yes, choose Aperture Priority (A or Av on your camera’s mode dial). It’s an auto exposure mode that enables you to manually choose an f-stop, with the camera selecting a corresponding shutter speed to achieve what it calculates as a good exposure, based on the aperture you’ve selected, metering mode, ISO and so on.

Although you can rely on Aperture Priority for day-to-day photography, you have to be mindful of how changing the aperture affects shutter speed.

You might, for example, select a small aperture when shooting a landscape, but if the exposure time then runs into seconds, you’ll need to support the camera on a tripod.

So is there an optimum aperture I should use?

The middle aperture range for your lens – usually from f/8 to f/11 – provides a good balance of depth of field and shutter speed.

Crucially, most lenses tend to deliver optimum quality images at these aperture settings, too (see box above).

Although lenses are classified using a fixed range of apertures, not all lenses are equal.

There’s a reason that a 50mm f/1.8 lens costs around £130, while a 50mm f/1.2 lens might set you back ten times that amount, at £1,300 – and that, in essence, is lens speed.

When photographers describe a lens as being ‘fast’ or ‘slow’, they’re not referring to the agility of its autofocus system, but rather how wide its maximum aperture is.

Fast lenses offer wide apertures that let more light in, giving you a faster shutter speed to work with.

They’re sought after for low-light work, exaggerated shallow depth of field effects and photography that frequently requires blazingly fast exposure times, such as wildlife and sports photography.

Slow lenses don’t capture as much light, so exposures require a slower shutter speed.

They’re usually lighter in weight than fast lenses though, and considerably kinder on your wallet.

So, a 10-20mm f/3.5 lens is faster than a 600mm f/4?

Ah, no. A lens is referred to as being fast or slow when it’s compared to lenses that have a similar focal length.

For its extreme focal length, a 600mm f/4 lens is fast, whereas a lens offering a maximum aperture of f/3.5 at 20mm is relatively slow; there are 20mm lenses available with faster maximum apertures of f/2.8 and f/1.8.

Many zoom lenses feature a ‘floating aperture’, so the maximum aperture changes as you zoom.

A 100-400mm f/4.5-5.6 lens offers f/4 as a maximum aperture, but this gradually narrows to f/5.6 as the lens is zoomed to 400mm.

Zoom lenses with floating apertures are generally slower and cheaper than zooms that maintain the same maximum aperture throughout their range.

If you need the fastest maximum apertures going, then you’ll be looking at high-quality prime lenses, rather than zooms. Start saving now…

What is an aperture made of?

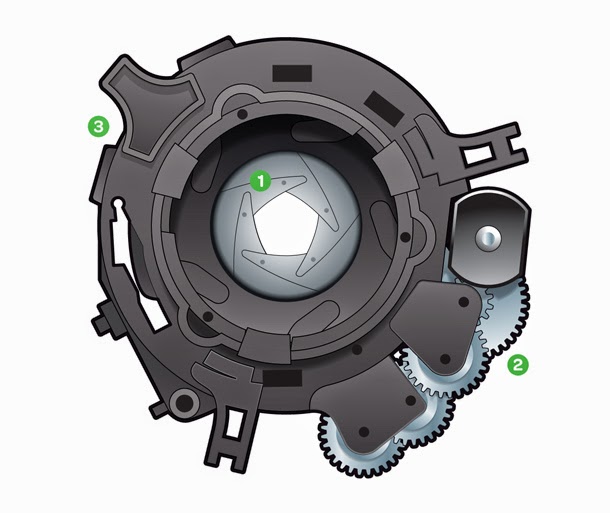

01 Blades

The aperture diaphragm is made up of between five and nine interleaved blades.

The more blades that are used, the smoother and more circular the ‘bokeh’, or out-of-focus areas, appear.

This opens and closes the aperture when the shutter fires, to ‘stop down the lens’ to the aperture you’ve selected.

By default, lenses show the view through the maximum aperture in the viewfinder.

02 Motor

This opens and closes the aperture when the shutter fires, to ‘stop down the lens’ to the aperture you’ve selected. By default, lenses show the view through the maximum aperture in the viewfinder.

03 Location

The aperture assembly doesn’t sit in your camera, but rather in the barrel of each of your lenses.

The range of aperture settings available varies depending on the particular lens being used.

How to control aperture

Manual exposure gives you total control over both aperture and shutter speed, but it can be a fiddly system when you’re just starting out.

Aperture Priority (A or Av) is a semi-automatic exposure mode that, as the name suggests, enables you to set the aperture as a priority.

Step 1

The easy way to control aperture yourself is by selecting A/Av mode on the Mode dial. Then simply rotate your camera’s main input dial to increase or decrease the aperture setting. The camera will automatically adjust the shutter speed as you do so.

Step 2

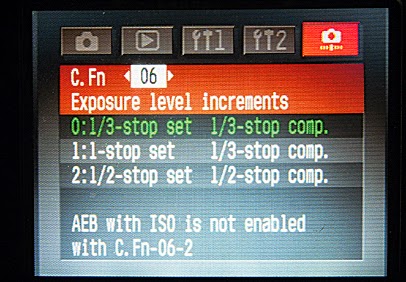

Digital SLRs offer a choice of up to three aperture scales, with full-stop, half-stop or third-stop increments (head to your camera’s Custom Functions menu to choose your preference). We prefer third stops as it enables fine-tuning of exposure.

Step 3

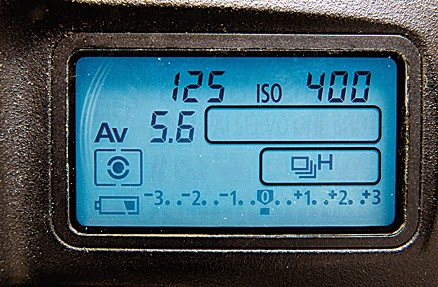

There are three ways to keep track of the aperture setting – in the viewfinder, on the rear LCD screen and, in the case of high-end DSLRs, on the small top-plate LCD screen. We like the clarity that a top screen and the viewfinder provide.

Step 4

Many cameras have a Depth of Field Preview button that closes the aperture down to the setting you’ve chosen, enabling you to gauge the depth of field through the viewfinder. However, Live View offers a more effective representation of the aperture setting.

Why a small aperture isn’t always best

Most lenses have a minimum aperture of f/22, although some (such as macro lenses) offer an even smaller setting of, say, f/32.

But why is the minimum aperture rarely listed alongside the focal length, as its maximum aperture is?

This is because the smallest aperture is rarely recommended to be used, as this setting leads to softer, lower contrast images caused by an optical phenomenon known as diffraction.

Diffraction occurs when light waves entering the lens are ‘bent’ by the hard edges of the aperture blades.

Every aperture setting causes this, but the bending is generally minimal. However, as the apertures get smaller, the effect becomes more significant.

At the smallest aperture, the light waves are bent and spread out so much by the aperture blades that the image appears fuzzy, even though it’s focused correctly.

So, while a lens’s smallest aperture might enable you to maximise the depth of field when you’re photographing landscapes, the resolution will deteriorate.

Try shooting at f/16 instead to improve overall picture quality.

What are f stops?

Dial through the f-stops in Aperture Priority mode and the sequence of numbers that appears in the viewfinder can appear quite random.

Why does f/5.6 jump to f/8 when you close the aperture by one full stop, then from f/8 to f/11 to f/16 and so on? There seems to be no logic to it.

How these numbers are calculated is actually pretty complicated, but the thing to bear in mind is that an f-stop isn’t a measurement of the diameter of the aperture, but an expression of the ratio between the diameter of the entrance pupil and the focal length.

This means that aperture values are constant no matter what lens is in use.

For instance, an 80mm lens with an aperture setting of f/4 will have a pupil diameter of 20mm (80÷4), whereas a 400mm lens with an aperture setting of f/4 will have a pupil diameter of 100mm (400÷4).

While the 400mm has a considerably larger pupil, it lets in exactly the same amount of light as the same f/4 aperture does on the 80mm lens, because the light is much dimmer by the time it has travelled the length of the lens.